The shift in arranged marriages

Table 1

In the rural, agricultural hub known as Greenfield, California, the District Attorney’s Office in January charged a Mexican immigrant from what Greenfield Police Chief Joe Grebmeier initially described as a case of “human trafficking” (Chawkins, 2009). Thirty-six-year-old Marcelino DeJesus Martinez allegedly attempted to sell his 14-year-old daughter to 18-year-old Margarito DeJesus Galindo for $16,000, 150 cases of beer, 150 cases of soda and Gatorade, and several cases of wine and meat. What’s more, Martinez was the one who brought the case to the Greenfield police, complaining that Galindo failed to come up with the goods. As a result, Martinez was charged with providing a child for lewd acts, aiding and abetting statutory rape, and causing or permitting cruelty to a child – two felonies and a misdemeanor (Parsons, 2009).

Newsrooms around the world – including Australia, Romania, South Africa, and India – put a spotlight on this interesting case. Some journalists denounced the deal between the father and the intended groom, with a United Arab Emirates blog asking, “What are you worth?”(Kipp’s Blog, 2009). However, virtually all of the articles, following journalistic guidelines for fairness, included at least a sentence about Martinez’ Mexican Triqui culture, in which arranged marriages are common.

The people involved in the case, including Martinez and Galindo, are some of the several thousand Triqui immigrants in Greenfield (Chawkins). The Triqui , or Trique (pronounced TREE-key) are a tight-knit, indigenous group of Oaxaca, Mexico, with strong ties to the earth and persisting traditions (Grasman, 2004). Like many indigenous tribes, the Triqui are of low social status and are mistreated by the general public (Szustek, 2009). According to linguist Barbara E. Hollenback, “Local speakers of Spanish tend to look down on all speakers of Indian languages, but especially on the Trique, and the local Mixtec also look down on them, leaving them at the very bottom of the social pecking order” (as cited in Szustek, 2009). Members of the group are often married as teenagers, and their bridal price is negotiated in four visits between families. Usually, the price determines the success of the marriage. Polygamous marriages are not uncommon. Overall, pressure and derision from the general population cause this and other social norms to remain entrenched within the Triqui community (Szustek).

Gaspar Rivera, a native of Oaxaca and project director of the UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education, said that the legal age of consent in the Mexican state is 16, though women as young as 12 have been known to be married off (as cited in Chawkins, 2009). Additionally, legal ramifications are often not an issue so long as the involved parties are all in consent; otherwise, arrangements are canceled. In the Greenfield case, the 14-year-old girl willingly vacationed with her intended suitor for a week in Mexico and apparently made no objections to the marriage (Szustek, 2009).

According to Andres Garcia, a Greenfield fieldworker and community activist, the Triqui in the Greenfield area have struggled to adapt (as cited in Chawkins, 2009)."Our people get discouraged because they don't understand, they don't speak English or Spanish, they don't read -- so they figure what's the use?"

Martinez speaks no English and only limited Spanish, resulting in delays in his arraignment (Chawkins, 2009).

While Martinez’ immigration status was not officially released, federal immigration agents put a hold on him, indicating that he is an illegal immigrant and is subject to deportation proceedings after local prosecution (Parsons, 2009).

After the incident, Grebmeier planned to have meetings with the town’s Triqui population to discuss the cultural differences behind this incident (Parsons). "You hate to demonize these folks," he said. "It never occurred to anyone involved they were breaking the law." He added, I’m trying to be culturally sensitive, but I also took an oath to enforce our law” (as cited in Taylor, 2009).

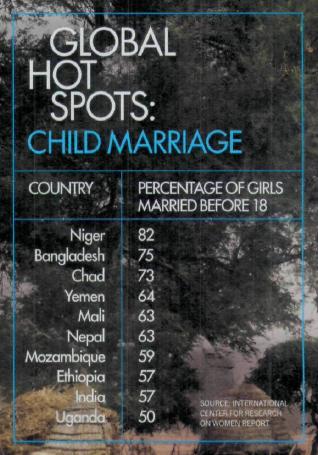

Mexico is by far not the only nation where cultures observe the tradition of arranged marriages. The International Center for Research on Women recorded the countries with the highest percentage of girls married before age 18 (see Table 1); most of the nations are African. Fifty-one million girls ages 15 to 19 worldwide are married or promised, often to older men (Amber, 2008, p. 185).

In Niger, arranged marriage is a tradition that has endured for centuries (Amber, 2008, p. 146). Girls as young as 12 are married to men as much as three times older than they are. Such marriages are encouraged for economic reasons, as famine is a constant threat; 85% of the land is incapable of being farmed, and in 2005, a food crisis affected more than 2 million people. Therefore, families try to arrange for their daughters to marry older men who are more likely to be able to provide for them. Also, as in other cultures, families with children who are not married by a certain age are stigmatized.

Proponents of arranged marriages credit them for their stability, compared to “love” marriages; the divorce rate of arranged marriages was 5-7%, compared to 50% in the United States (Seth, 2008, p. 78).

Public outcry against arranged marriages has increased over the years, through the media and the work of organizations and individuals. Such protests are based on the ideas that real consent cannot be given by young girls, and that arranged marriages “pose serious societal, economic, and health risks for girls, who are often pulled out of school when they are wed and impregnated before their bodies are fully developed” (Amber, 2008, p. 146). In Niger, one in seven women die during pregnancy or childbirth, compared with one in 4,800 in the United States; such risks are magnified for girls ages 10 to 14 (Amber, 2008, p. 148). Additionally, there are only 500 doctors to serve the Nigerian population of 13 million.

Activists and politicians work to end arranged marriages worldwide (Amber, 2008, p. 46). Organizations such as UNICEF and Save the Children condemn the marriages as abuse and violation of human rights. Congresswoman Betty McCollum (D-MN) introduced legislation in 2007 to reduce the incidence of child marriage, saying, When young girls become wives, it is socially sanctioned sexual abuse” (as cited in Amber, 2008, p. 146). Efforts to educate girls or provide them with jobs to help steer them away from arranged marriages are lauded.

In some cultures, arranged marriages are in decline. For instance, in the urban Chinese city of Urumchi in 2005, data has shown a rapid decline in arranged marriages for two Chinese ethnic groups, Uyghur Muslims and Han Chinese (Zang, 2008, p. ). The same trend is seen in Japan. Before World War II, weddings often took place between people who had never met before the ceremony. Since then, omiai, or arranged marriages, have been increasingly replaced by “love marriages.” Half a century ago, nearly 70% of Japanese marriages were arranged; today, less than 10% are (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1998).

For centuries, arranged marriages have been a customary norm in South Asia, considered ritual and sacramental unions by many Asian cultures (Bhopal, 1999). Today, more than 90% of Indian marriages are arranged (Gautam, 2002, p. 32). While purely romantic love is still generally considered “impractical, unnecessary, and dangerous,” the nature of them is changing toward more dominant, Western ideals (Desai, McCormick, and Gaeddert, 1989, p. 94). Though trends vary by social class, middle-class marriages have particularly developed to be more companionate (Fuller, 2008). They have “progressed” so that parents and children choose a spouse together, following an ideal of “companionate ‘emotional satisfaction’ that is not premised on young people’s unfettered personal choices.” According to Canadian political theorist C.B. MacPherson, companionate marriages reflect a rise in a kind of “affective individualism” that is less extreme than that of Western society, which can be considered as “possessive individualism” (as cited in Fuller, 2008). Additionally, University of Chicago economist Divya Mathur sees “love” marriages as capable of spurring economic growth in India; in traditional arranged marriages, parents prefer that daughters be less educated so they can have more control over household affairs, but if more women hold college degrees, they can provide for themselves and help redistribute resources more evenly in society (The Agenda, 2008, p. 31).

Additional resources

- Arranged marriage - New World Encyclopedia

- Cultural Clash Comes to Fore in “Teen Bride Sold for Beer” Case in California

The story of an immigrant from rural Mexico selling his teenage daughter into marriage for cash, beer and meat has brought to light the travails in assimilation into American culture. - Arranged marriage - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia